Xavier Luffin (Université libre de Bruxelles)

From the end of the 19th century and throughout the colonial period, European observers generally described – with a few exceptions – the Arab and Swahili traders settled in Congo as people essentially, if not exclusively interested in trade, pious indeed, but little concerned with culture. A first glance at the documents found in the various Belgian colonial archives – those of the Royal Museum for Central Africa (now AfricaMuseum) in Tervuren and the African Archives in Brussels in particular – seemed to prove them right: trade letters, contracts, lists of merchandise, and treaties made up the bulk of the documents that are preserved.

But a closer look at the archives quickly contradicted this initial impression. First of all, a number of books in Arabic – copies of the Koran, prayer books, astrology and magic books – from Maniema and Stanleyville, as well as from the far north-east of the country (Uele and the enclave of Redjaf-Lado, now part of South Sudan but attached to the Congo Free State until 1908), were also among the Arabic and Swahili documents brought back at the end of the 19th century. Lastly, certain passages of varying length from Arabic texts, and more rarely from Swahili, were to be found in certain documents of a seemingly commercial nature.

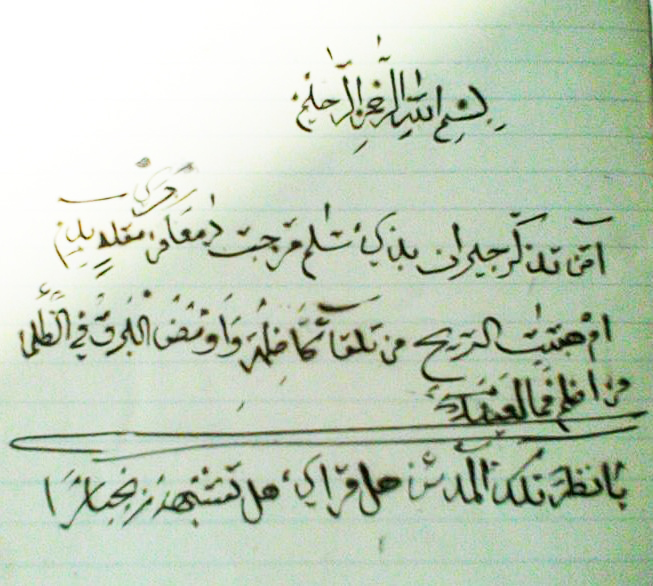

One such document is a notebook found in Stanley Falls (now Kisangani), that belonged to two traders from the Swahili Coast, as indicated by a notice on the second page: “dated the 12th of the month of jumādā al-ākhar 1309 [January 13, 1892]. This notebook belongs to the humble servant of God Most Great, Sa’īd bin Thābit bin Sulaymān, and to Ḥabīb bin Sa’īd bin Hāmīd.” Sa’īd bin Thābit bin Sulaymān, also known as Saidi bin Sabiti in Kiswahili, is a well-known figure in the history of the city of Kisangani: nephew of Tippo-Tip, he was appointed representative of the Muslims of Stanleyville by the colonial authorities as early as 1894, and remained so until his death in 1899. His descendants continue to play an important role in the community to this day. The notebook, now kept at the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, was brought back to Belgium by a Belgian officer, Nicolas Tobback (1859-1905), who was stationed at Stanley Falls from 1888 to 1893.

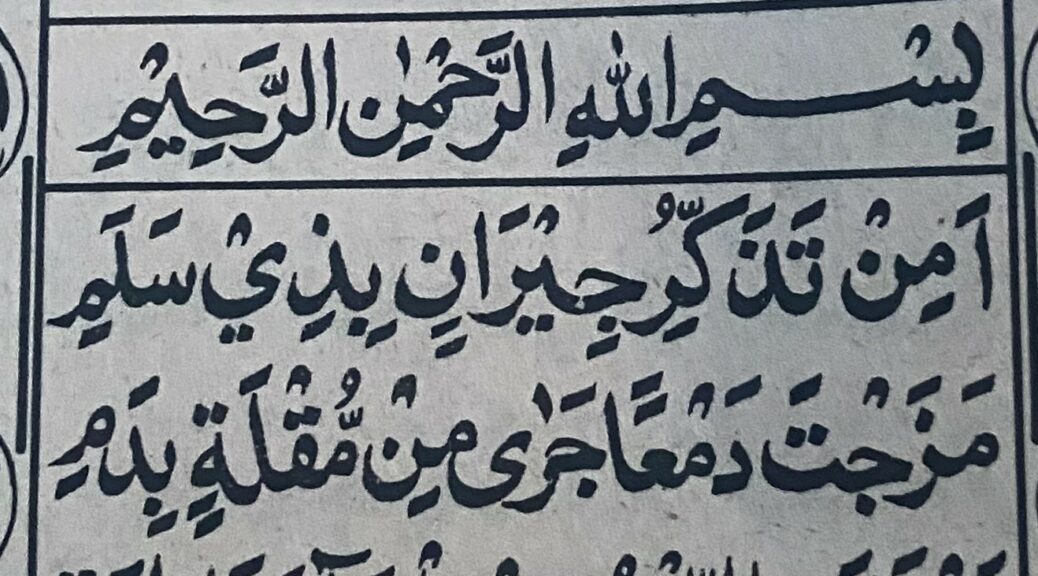

It’s a European-style notebook, measuring 16 cm by 20 cm, filled with lined sheets and fitted with a black canvas cover. The notebook’s owners wrote down all sorts of things, mostly in Arabic, but also sometimes in Swahili with Arabic characters: lists of goods, transactions related to the purchase of ivory in exchange for cloth, drafts or copies of missives, but also magic squares, passages from a book of magic, and so on. On the 14th page (illustration 1), following the recording of a commercial transaction and before a magic square on the following page, there are two verses of Arabic poetry, preceded by the basmalla (the invocation of God in Arabic: “In the Name of God, Clement and Merciful”):

أَمِنْ تَذَكُّرِ جِيرَانٍ بِذِي سَلَمِ مَزَجْتَ دَمْعًا جَرَى مِنْ مُقْلَةٍ بِدَمِ

أَمْ هَبَّتِ الرِّيحُ مِنْ تِلْقَاءِ كَاظِمَةٍ وَأَوْمَضَ البَرْقُ فِي الظَّلْمَاءِ مِنْ إِضَمِ

These two verses are in fact the incipit of a long poem – 161 verses – very famous throughout the Muslim world, by an Egyptian Sufi poet of North African origin, Sharaf al-Dīn al-Būṣīrī (1213-1294), who praises Muḥammad. Here is the English translation of these two verses, made by the renowned British Orientalist J. W. Redhouse (1811-1892) in 1880[1] :

« Is it from a recollection of neighbours at Dhū-Salam that thou hast mixed with blood the tears flowing from an eyeball?

Or, has the wind blown from the direction of Kādzima, and has the lightning gleamed in the darkness from Itzam? »

The poem goes on:

« What ails thy two eyes? If thou sayest, ‘Leave off,’ they fill. And what ails thy heart? If thou sayest, ‘Be tranquil,’ it is perplexed.

Does the deeply-entangled lover suppose that affection can be concealed, when it is being partly wept for, and partly suffered for?

Were it not for fondness, thou hadst not shed tears over projecting ruins, neither hadst thou remained sleepless with the memory of the moringa-tree and the long hill.

And how wilt thou deny love, when the truth-speaking witnesses, tears and wasting, have testified to it against thee,

And ardour hath fixed upon thy cheeks the two lines of grief and woe, like unto the corn-marigold and the ‘anam?“

Yea! The phantom of her I love passed before me, and made me sleepless. For love doth dash delights with pain… »

The poem is generally referred to as Qaṣīdat al-Burda (“The Ode of the Mantle”) or simply al-Burda (“the Mantle”), although its true title is actually Al-kawākib al-durriyya fî madḥ khayr al-bariyya, “The Shining Stars in Praise of the Most Perfect of Creatures.” The poem’s popular name derives from an event surrounding its composition, according to some commentators: the poet, suffering from paralysis, composed this poem one day, then began to invoke God in order to heal him. Once asleep, he saw Muḥammad in a dream placing a cloak over him after laying his hand on his ailing body. When he awoke, al-Būṣīrī was cured…

The 161 lines that make up the poem all end with the rhyme -mi, constituting what is known in Arabic as a mīmiyya[2], and are subdivided into several parts: a prelude, which follows the canons of classical Arabic poetry, followed by Muḥammad’s virtues, a description of his birth, the miracles attributed to him, a description of the virtues of the Koran, Muḥammad’s Night Journey, the battles he won, his power of intercession and finally prayers.

The poem was, and still is, recited or sung throughout the Muslim world, particularly in Sufi circles, on various occasions, including Mawlid, the celebration of Muḥammad’s birth. Numerous copies of the poem circulated and still circulate in East Africa, including in the libraries of certain mosques such as Riyadha Mosque in Lamu (Kenya), suggesting that it was part of the curriculum for students in the region.

The poem also addresses the question of intercession – al-tawassul or al-shafâ’a in Arabic, from which the poet himself benefited according to the account given above – as in verses 86-87, again according to Basset’s translation:

« How many hath his [Muhammad’s] hand cured by the touch who were diseased; and hath skilfully set free from the halter of insanity!

And his prayer hath made the year of drought to be alive—so that it hath been told of as a chief [year] among the times of rich vegetation. »

This is why some of these verses are also used to ensure the healing of the sick or to make talismans, as explained by Redhouse in the introduction of his translation. A late work by the Egyptian scholar al-Bājūrī (d. 1860) devoted to al-Būṣīrī’s poem explains how to take advantage of al-Burda’s verses for therapeutic, but also magical purposes: to protect oneself from thieves, from certain illnesses such as epilepsy, from wild animals, but also to give courage to warriors and even help foreign slaves learn Arabic easily… This may also explain why only the first two lines of the poem appear in the notebook, which is otherwise full of squares and magic formulas: Saidi bin Sabiti undoubtedly knew the whole poem or part of it by heart, but he had deliberately noted down only the two lines used for a specific request for intercession.

Such was al-Burda’s success in the Muslim world that it led to its translation into many languages: Persian, Turkish, Malay, and later, probably in the 19th century, Swahili – several manuscript copies have been found in various archives on the Tanzanian coast – and has been the subject of much commentary. Here are the first two verses in Swahili[3] :

« Ni kwa kukumbuka jirani wema

walioko hapo bi Dhi Salama

umelitanganya tozi kwa dama

kwamba ma‘anaye ni haya sema.

Amma ni upepo kupita kwake

kutoka Kadhima janibu zake

amma ni umeme kwa nuru yake

kuinuka kiza hapo Idhama ? »

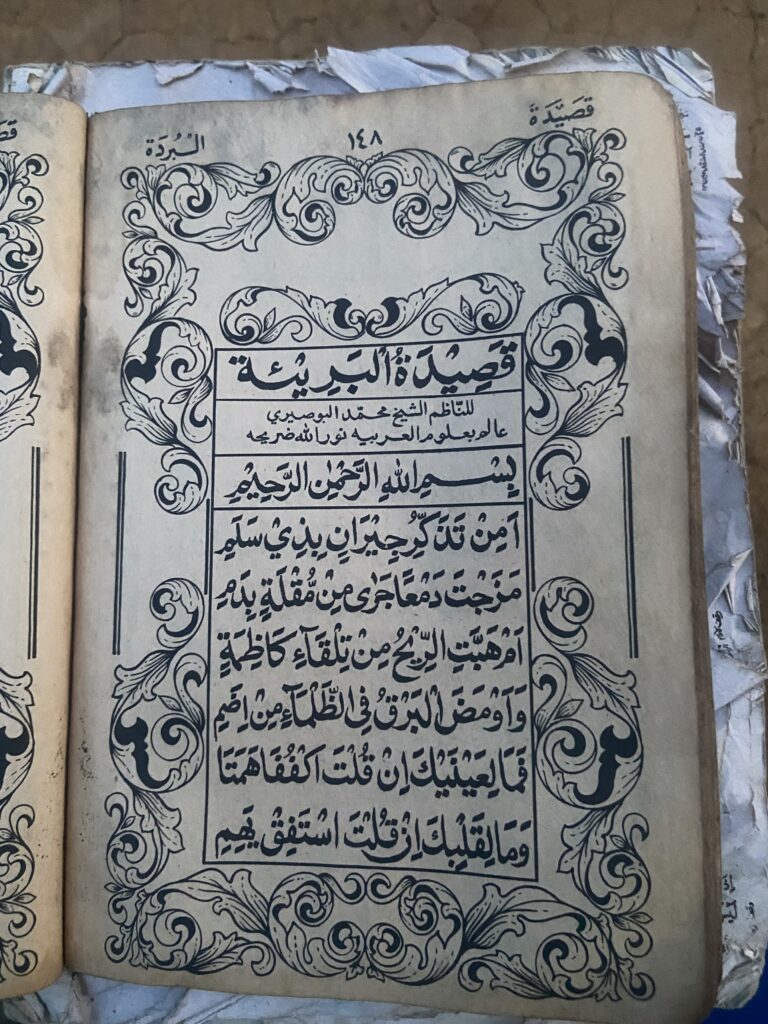

The Swahili translation has been expanded with an eleven-line prologue in which the translator explains his approach (in the third line, he says: “I have translated and explained [this poem], I have clarified its meaning, because Arabic has a hidden meaning that not everyone can grasp”) and a 19-line epilogue. I have not – not yet – found any trace of this Swahili translation in Congo. In September 2023, in Kisangani, I showed a photograph of the page to Oyoko Hamzati Hamza, who immediately recited, from memory, the first verses of the Burda in Arabic, following a particular prosody. In the days that followed, I saw these same verses reproduced in various copies of Majmū’ al-mawlid printed in India (illustration 2), a collection of poems read on the occasion of Mawlid. A few months later, I saw similar copies again in Kasongo, Maniema. So, poetry has had its place in the culture of the Muslim community for over a century…

Ill. 2: al-Burda, taken from a copy of Majmū‘ al-mawlid, Kisangani 2023]

By way of an epilogue, I’d like to mention the astonishing continuation of this poem’s journey from Africa: as early as the 18th century, many of the slaves sent from the Gulf of Guinea to the Americas were Muslims, and some of them literate. In recent years, several interesting studies have been carried out on the few documents they left behind, notably talismans composed by Hausa scholars, the Malé, who instigated a famous slave revolt in Bahia, Brazil, in 1835. It was following the suppression of this revolt and the arrest of the insurgents that several of their talismans written in Arabic characters were seized as evidence and preserved. One of them contains a verse from the famous Qaṣīdat al-Burda, which one of these erudite slaves taken from West Africa to work on Brazilian plantations had memorized and reused, in the manner of the two verses in our notebook, thousands of miles from his native land, for its protective virtues…[4]

Notes

[1] Published in W. A. Clouston, Arabian Poetry for English Readers, Glasgow, 1881.

[2] A poem whose each verse ends with -mi.

[3] J. Knappert, Swahili Islamic Poetry, Leiden, Brill, II, p. 165. The Hamziyya of al-Būṣīrī, mentioned above, was also translated into Kiswahili.

[4] See for instance N. Dobronravin, « Nao so Mandingas… », Afro-Ásia, 53 (2016), 185-226.